Alternating series

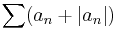

In mathematics, an alternating series is an infinite series of the form

with an ≥ 0 (or an ≤ 0) for all n. Like any series, an alternating series converges if and only if the associated sequence of partial sums converges.

Contents |

Alternating series test

The theorem known as "Leibniz Test" or the alternating series test tells us that an alternating series will converge if the terms an converge to 0 monotonically.

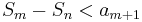

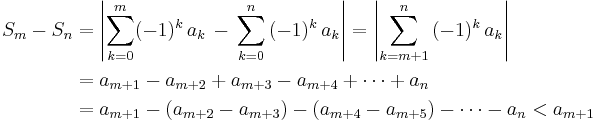

Proof: Suppose the sequence  converges to zero and is monotone decreasing. If

converges to zero and is monotone decreasing. If  is odd and

is odd and  , we obtain the estimate

, we obtain the estimate  via the following calculation:

via the following calculation:

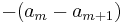

Since  is monotonically decreasing, the terms

is monotonically decreasing, the terms  are negative. Thus, we have the final inequality

are negative. Thus, we have the final inequality  . Since

. Since  converges to

converges to  , our partial sums

, our partial sums  form a cauchy sequence (i.e. the series satisfies the cauchy convergence criterion for series) and therefore converge. The argument for

form a cauchy sequence (i.e. the series satisfies the cauchy convergence criterion for series) and therefore converge. The argument for  even is similar.

even is similar.

Approximating sums

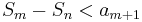

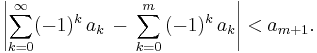

The estimate above does not depend on  . So, if

. So, if  is approaching 0 monotonically, the estimate provides an error bound for approximating infinite sums by partial sums:

is approaching 0 monotonically, the estimate provides an error bound for approximating infinite sums by partial sums:

Absolute convergence

A series  converges absolutely if the series

converges absolutely if the series  converges.

converges.

Theorem: Absolutely convergent series are convergent.

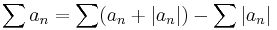

Proof: Suppose  is absolutely convergent. Then,

is absolutely convergent. Then,  is convergent and it follows that

is convergent and it follows that  converges as well. Since

converges as well. Since  , the series

, the series  converges by the comparison test. Therefore, the series

converges by the comparison test. Therefore, the series  converges as the difference of two convergent series

converges as the difference of two convergent series  .

.

Conditional convergence

A series is conditionally convergent if it converges but does not converge absolutely.

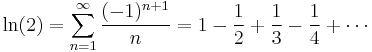

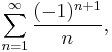

For example, the harmonic series

diverges, while the alternating version

converges by the alternating series test.

Rearrangements

For any series, we can create a new series by rearranging the order of summation. A series is unconditionally convergent if any rearrangement creates a series with the same convergence as the original series. Absolutely convergent series are unconditionally convergent. But the Riemann series theorem states that conditionally convergent series can be rearranged to create arbitrary convergence.[1] The general principle is that addition of infinite sums is only associative for absolutely convergent series.

For example, this false proof that 1=0 exploits the failure of associativity for infinite sums.

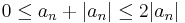

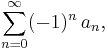

As another example, we know that  .

.

But, since the series does not converge absolutely, we can rearrange the terms to obtain a series for  :

:

Series acceleration

In practice, the numerical summation of an alternating series may be sped up using any one of a variety of series acceleration techniques. One of the oldest techniques is that of Euler summation, and there are many modern techniques that can offer even more rapid convergence.

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Mallik, AK (2007). "Curious Consequences of Simple Sequences". Resonance 12 (1): 23–37. http://www.springerlink.com/index/D65WX2N5384880LV.pdf.

![\begin{align}

& {} \quad \left(1-\frac{1}{2}\right)-\frac{1}{4}%2B\left(\frac{1}{3}-\frac{1}{6}\right)-\frac{1}{8}%2B\left(\frac{1}{5}-\frac{1}{10}\right)-\frac{1}{12}%2B\cdots \\[8pt]

& = \frac{1}{2}-\frac{1}{4}%2B\frac{1}{6}-\frac{1}{8}%2B\frac{1}{10}-\frac{1}{12}%2B\cdots \\[8pt]

& = \frac{1}{2}\left(1-\frac{1}{2}%2B\frac{1}{3}-\frac{1}{4}%2B\frac{1}{5}-\frac{1}{6}%2B\cdots\right)= \frac{1}{2} \ln(2)

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/20141ce0acdd9eb4a78b6a88f54c7810.png)